Baseball is often seen as a quantitative sport. Thanks to the popularity of Moneyball, Sabermetrics, and Statcast, we often find ourselves boiling down players and their careers into a bottomless pile of numbers.

OPS, xwOBA, DRS, UZR, SIERA – the list of funky metrics to define an aspect of an individual's performance is nearly endless and more come out with each passing year. In fact, we now have so much information that you can almost tell the whole story of a player without ever having watched them play.

Almost.

Ichiro Suzuki's arrival chartered a new course for Major League Baseball

Ichiro Suzuki's story by the numbers is already quite impressive. Depending on who you ask, he's professional baseball's hit king. With 3,089 MLB hits and 1,278 NPB hits, his total of 4,367 is more than Pete Rose's 4,256 in the majors. What's less disputed is the 262 hits he accumulated in a single season, five more than George Sisler's seemingly unbreakable record of 257 that stood for 84 years. He also strung together 10 consecutive seasons with 200-plus hits. In those same seasons, he also won 10 Gold Gloves for his stellar work in right field and received 10 All-Star nods.

However, in a vacuum and with a modern lens applied, there are a lot of aspects of his career that may make his overwhelming entry into the Hall of Fame on his first attempt somewhat questionable. Yes, he did eclipse major milestones including having 3,000 hits and 500 stolen bases, but his career rWAR of 60.0 and OPS+ of 107 are in line with other players who have struggled to gain entry into Cooperstown.

Numbers like these are what made Ichiro Suzuki a near-unanimous Hall of Famer! pic.twitter.com/F2Kk1uRIsZ

— MLB (@MLB) July 19, 2025

Kenny Lofton (68.4 rWAR, 107 OPS+) has similar numbers, but fell off the ballot after one year. Andruw Jones (62.7 rWAR, 111 OPS+) has inched closer with every year since he first appeared in 2018, but hasn't managed to cross the 75 percent threshold just yet. Jim Edmonds (60.4 rWAR, 132 OPS+) received just 2.5 percent of the vote in his only eligible year. The gap between the reputations of so many statistically similar players and Suzuki's own illustrates just how much his enshrinement is about so much more than numbers.

As unique as his approach at the plate was, it was far from perfect and still not enough to make him the most productive player in a century that includes the likes of Albert Pujols, Mike Trout, and Aaron Judge. It has long been speculated that had Ichiro drawn more walks and hit for more power, he could have been an even more impactful presence at the plate.

According to Barry Bonds, who served as Ichiro's hitting coach while he was on the Miami Marlins, he had more than enough power to do so but actively chose not to. He ranks 25th all-time in hits, 35th all-time in stolen bases, 90th all-time in runs scored, and isn't even in the top 500 all-time for home runs and RBI. His skillset was awesome, but that's not what made him great.

What made him great was the cultural shift that he started all the way back in 2001 in his rookie season for the Seattle Mariners.

Baseball has always been a global game. Perhaps not as global as soccer, basketball, or even cricket, but it has a diverse history, rich with great players from all backgrounds. Japan has had an organized professional league since 1936, but there was a notable lack of Japanese players in MLB for decades after. Even after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier and Latin players like Orlando Cepeda and Juan Marichal began their Hall of Fame trajectories, the only Japanese big leaguer before 1995 was Masanori Murakami, who played just two seasons as part of an exchange program.

Hideo Nomo was the first modern player to come over from NPB and after his Rookie of the Year campaign in 1995, it opened the door for other Japanese pitchers like Tomokazu Ohka and Seattle's own Kazuhiro Sasaki. However, despite the moderate success of these players, the overall belief was that Japanese hitters wouldn't be able to compete with the higher velocity of Western pitchers.

Even after signing, Ichiro's own manager Lou Piniella expressed skepticism about his ability to be an especially good hitter. By winning both the AL Rookie of the Year and the MVP in 2001, Ichiro quickly put those concerns to rest. He played the game with a level of refinement and precision that was initially unexpected but quickly became the norm for him. Even his intricate warm-up routine quickly became well-known across other sports.

April 2, 2001: Ichiro becomes the first Japanese-born position player to play in the majors.

— MLB Vault (@MLBVault) April 2, 2023

He would hit .350 with 56 stolen bases that year, earning Rookie of the Year and MVP honors. pic.twitter.com/ZxnYSAMw7M

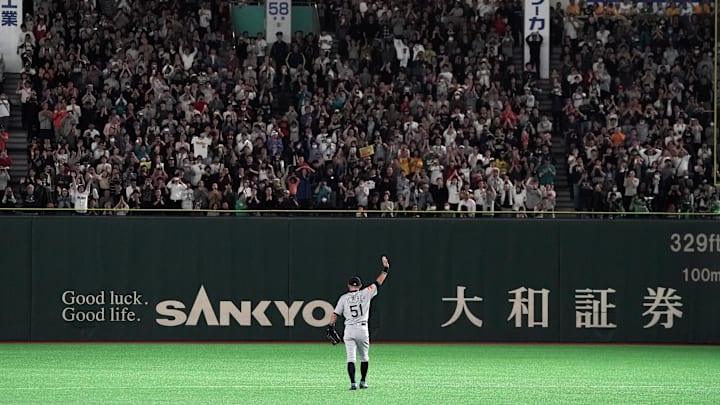

Now, Japan is well-known as a baseball powerhouse. The nation has won three World Baseball Classic trophies — including the tournament's most recent iteration in 2023 — and has plenty of current big league representation, and even lays claim to perhaps the most talented player of all time in Shohei Ohtani. Had Ichiro Suzuki not taken the leap of faith in 2001 and, against all odds, solidified himself as one of most impressive players to ever take the field, we may not have had the chance to see such talent from the other side of the world thrive in Major League Baseball.

As much as we've tried to quantify and compartmentalize every aspect of the sport, it's ultimately the stories of the game that made us fall in love, and those same stories are what keep us around. With his story, it's no wonder that Ichiro is the first ever Asian-born player to be inducted into the Hall of Fame and was nearly the second-ever person to be unanimously inducted.