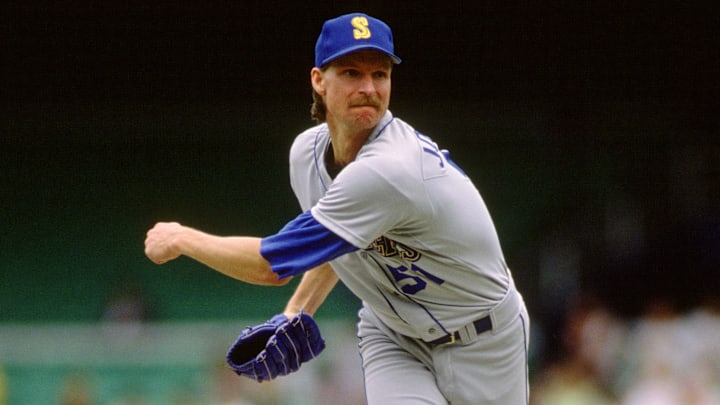

The Seattle Mariners have officially picked May 2, 2026 as the day they will retire Randy Johnson's No. 51. And when it happens, it will put a nice bow on a partnership that probably never should have worked.

It indeed never would have happened at all if the Montreal Expos hadn't been in the market for pitching help early in the 1989 season. The Mariners obliged, sending Mark Langston and a player to be named later to the Expos in a trade that brought back three pitchers: Gene Harris, Brian Holman and Johnson.

"We looked at a lot of packages, but we had to get pitching,” was how Woody Woodward, the Mariners' director of baseball operations, justified the trade at the time. And while Johnson had been a prospect of some renown, the Expos were not convinced that he was the best pitcher they had traded away.

"Randy was very talented and threw very hard, but when you looked at it in-depth, if you asked different people in our organization then to rank Brian Holman, Gene Harris and Randy Johnson, different people would have given you different orders of one, two and three," said Dave Dombrowski, who was the GM of the Expos in 1989.

Randy Johnson had to beat overwhelming odds to become a Mariners legend

Johnson did not fit into a tried-and-true mold when the Expos took him out of USC in the second round of the 1985 draft. He was, after all, a 6-foot-10 pitcher entering a league in which nobody over 6-foot-8 (shoutout to J.R. Richard and Gene Conley) had ever achieved real success on the mound.

And if you know anything about Johnson's early years in MLB, you won't be surprised that his early scouting reports don't read like glowing endorsements. They are a blend of excitement, befuddlement and hedged bets.

Courtesy of Baseball America, here's a report from Rico Petrocelli, then the manager of the Double-A Birmingham Barons, in 1987:

"Has more potential than any pitcher in the league. Has control problems, but can throw 93-plus (mph) on the fastball. Is a good competitor. It will take time before he puts it all together, but he can be a real good one. He’ll either be a great one or one that will just never put it together--no in-between."Rico Petrocelli in 1987

This was after a year in which Johnson, who was still years away from being known as the "Big Unit," had struck out 163 batters and walked 128 batters in a sample of 140 innings. Between his time in the minors and the majors, it was one of four seasons in which he issued at least 120 free passes — a mark of shame that is now all but extinct.

Baseball America's own scouting reports for 1987 and 1988 conclude with a note that some scouts believed Johnson to be destined for work in short relief. And even after he made his first All-Star team with the Mariners in 1990, he wasn't necessarily on his way to all-time greatness as a starter.

Whereas they remained relatively subdued in 1990, Johnson's control issues roared back in 1991 and 1992. He averaged 6.5 walks per nine innings across those two seasons, which is more walks per start than the Mariners got from any of their starters in any game during the 2025 season. And while his swing-and-miss stuff helped keep runs off the board, he was still close to average by way of a 104 ERA+.

What changed everything for Johnson was the guidance he received from Nolan Ryan and Tom House, then the ace and pitching coach for the Texas Rangers, in 1992. They contributed to a change in his mechanics, with his lead foot landing on the ball instead of the heel. The results were pretty much instant, as Johnson finished the 1992 season with an 11-start run in which he had a 2.65 ERA, 117 strikeouts and 47 walks in 85 innings.

The rest of Johnson's story tells itself. He was the runner-up for the AL Cy Young Award in 1993, and then he won it in 1995 after what might be the single best season a Mariners player has ever had. It was the first of five Cy Young Awards, and those are just five of many reasons he got into the Hall of Fame with 97.3 percent of the vote in his first year on the ballot in 2015.

That Johnson's plaque in Cooperstown depicts him in an Arizona Diamondbacks hat instead of a Mariners hat is only fair, given that he won four of his Cy Youngs and his lone World Series ring as a Diamondback. And as he would like everyone to know, it was not by choice that he left the Mariners in 1998.

Whatever the case, Johnson's number retirement in Seattle has been a long time coming. He was by far the best pitcher in Mariners history when he left in 1998, and you can make the case that he still is nearly 30 years later. For a guy who was once seen as a possible reliever, it's not exactly a bad outcome.